A brief prolegomenon – what are we talking about?

Tonality is all about hierarchy of notes. In Western culture, we use a scale called “diatonic”, with five tones and 2 semitones (12 halftones in total). Eastern music is based on a scale of five notes (pentatonic). In India, quarter tones are used (in the western hemisphere these notes are perceived as “out of tune”). All around the world we can find music based on the use of specific scales called “modes” (in the western culture the preponderant modes are “major” and “minor”). But, in all cases, not all notes have the same importance. Once a tonal center is established, some notes become more relevant than others. Dodecaphony or “Twelve Note Technique”, created by Arnold Schoenberg in 1921 and expanded by the Second School of Vienna, is based on the “democracy of notes”. This School gave a vigorous impulse to the atonal music trend that began to be explored in the early 20th century by composers like Scriabin, Stravinsky or Bartók.

One of the basic principles of the dodecaphonic model, is that all 12 halftones must have the same importance. Therefore, the concept of tonality becomes useless and that is why dodecaphonic music and “atonality” go hand in hand. However, both terms are not identical because dodecaphonic music is constructed upon structures, or series. There are other types of atonal music where there is no underlying pattern.

99% of progressive music is tonal, so we are all familiar with tonality. For those of you who have never heard atonal music, here are some examples:

Anton Webern – Six Bagatelles for String Quartet

Pierre Henry, « Variations pour une porte et un soupir »

Arnold Schoenberg: Serenade op.24

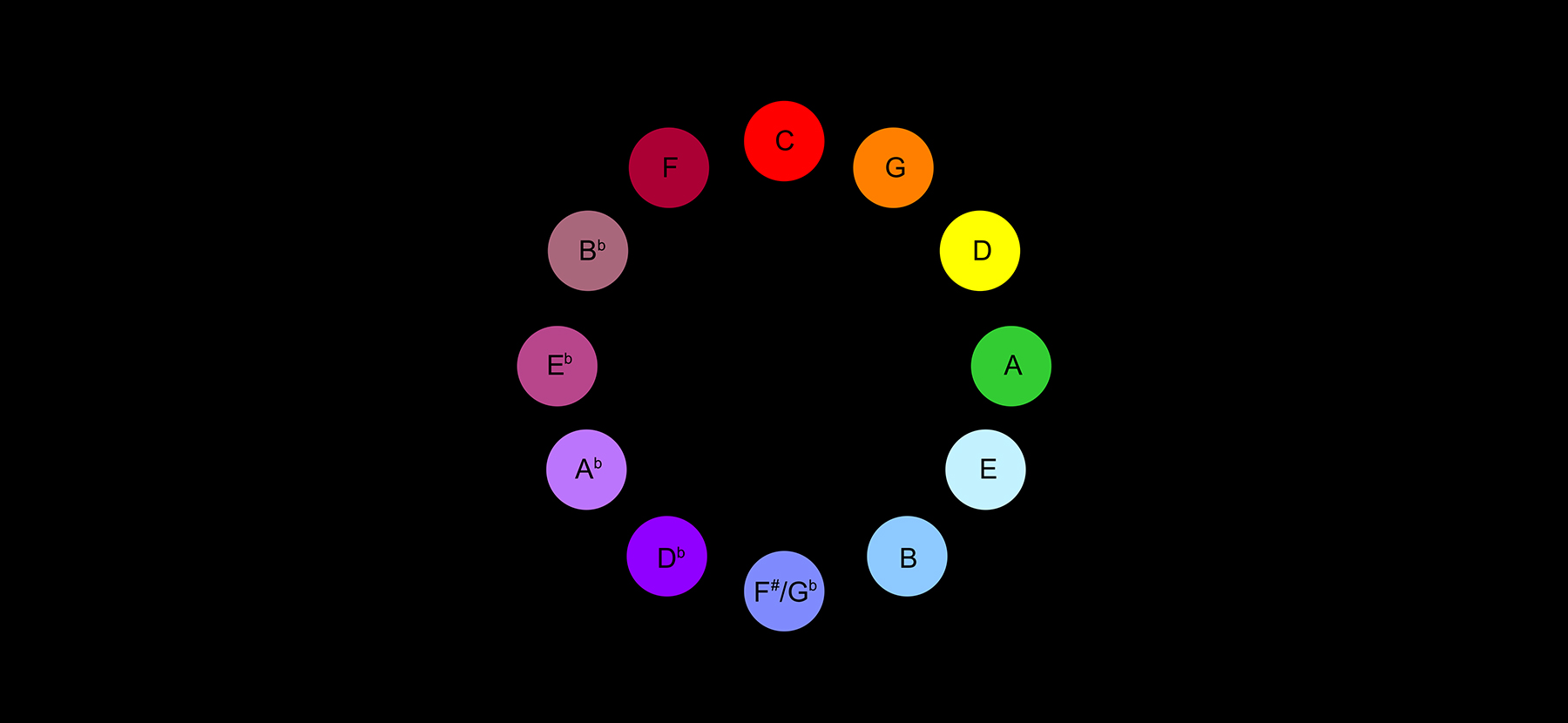

For several decades, the question of “Tonality” vs. “Atonality” has been the subject of analysis and debates by musicologists, musicians and philosophers. The fact that atonal music (dodecaphonic, serial, concrete, etc.) has not been able to impose itself over tonal music after a century, has led many to believe that atonal music is “unnatural”. Many believe that the way we perceive the hierarchy between notes, is related to how harmonics are produced. In other words, that tonality is a natural outcome of a physical manifestation: a sound is produced by a fundamental tone, and the sum of its harmonics. In the simple case of a string, the first harmonic is an octave higher than the fundamental tone, the second one is on an interval of a fifth. If we play a C, its second harmonic is a G. In a piece of music based on the C tone, the most relevant note, after C itself, is G.

Others claim that tonal chords produce a natural resonance on physical objects; for example, an orchestra that plays a “tutti” (all instruments playing at once) over a tonal chord, will resonate much more than the same instruments playing a “cluster” (a group of contiguous notes – like banging a piano with your fist).

These assertions may or may not be correct, but there is a fact that cannot be denied: an enormous amount of atonal music has been written since the beginning of the last century and yet, just an insignificant amount of listeners favor it over tonal music. With the exception of music ensembles that specialize in “contemporary music” (I don’t agree with the term – more on future articles), most orchestras and chamber groups base their repertoire on tonal music.

History shows that artists expand the known esthetics bounds, compelled by the need to communicate something that cannot be adequately portrayed with the tools at their disposal. Usually, it takes time for society to assimilate this new language and many artists die before their work is fully understood and appreciated. But the lag between the artist’s innovative language and human assimilation is usually measured in years or, at the most, decades. Never centuries, as would be the case with atonal music.

We can safely say that there is “something” about atonal music that just doesn’t click. I believe it is not about equating tonality with something natural and atonality with some sort of “Contra Naturam”. In fact, in a certain way as you will see later in the article, atonal music could be considered as very natural. Then, if this “something” about atonal music has nothing to do with tonality being more “natural”, what is it?

Let’s explore this concept about what is “natural” a bit further. Of course, as an adjective, the common definition is “Existing in or derived from nature; not made or caused by humankind” (Oxford Dictionary). However, for the purposes of this discussion, this definition is more appropriate: “Conforming to the usual or ordinary course of nature” (Free Dictionary). What is the ordinary course of nature? I would say a course that does not oppose the laws of physics and thermodynamics. A course that “flows naturally” with these laws. If you find this to be a sensible argument, then one may conclude that life is very unnatural. Let me explain what I mean.

It takes a lot of effort to stay alive. If you decided to lay in your couch and do nothing, in a few days your body would begin a very natural process: our highly organized molecular structure would decay into its simpler constituents. In order to keep your highly organized structure, you must eat and breathe. And, if you follow your instinct to preserve the species, in addition you must fight and mate. If you add to it the need to preserve your body from extreme heat or cold, you end up with a pretty full list of “To-Do’s” in order to stay alive. No wonder it is usually called “Struggle for Life”.

So, here we are, struggling to keep nature from doing its natural job: to decay into lower forms of potential energy.

Life seems to emerge from the manifestation of potential energy. Contrast incites movement, which in turn propels life. There is endless literature where this contrast is beautifully expressed. It’s all about contrast: day/night, light/dark, male/female, Ying/Yang…. As electric circuits cannot work without voltage, life cannot exist without contrast.

Which takes me to a beautiful concept about God and the Purpose of Life. Even if you are an atheist or agnostic, please bear with me. You may find these concepts interesting and intellectually challenging. Let’s assume that there is an underlying energy that brings coherence to the Universe. And, let’s also suppose that there is such a thing as an infinite Creator. An entity that “Is” and that cannot be called an entity because there is no beginning or end to It. Pure infinity in terms of space and time. Following our previous argument, such a “concept” (for lack of a better word) would have zero potential. No voltage. White noise.

What’s the use of being the best pianist in the world if you can never play because you don’t have a piano? Well, this “infinity” situation posed a bit of a problem for God: I cannot manifest what I Am, until I’m not all that I Am. I need contrast and that necessarily means a subset of what I Am.

So, God creates universes (yes, there may be more than one), each a subset of what He is, thus creating contrast, which in turn creates life. The ultimate purpose of this is to allow God to manifest Himself. And manifest what? Everything that can potentially be manifested, from Beethoven, to Emerson, to a cockroach. I’m here writing this because I’m nothing else than God manifested through me. And you. And Emerson. And a cockroach. Of course, this idea is not at all original, but it is interesting to see that, for most westerners, God is some sort of anthropomorphic entity that decides what is good or bad, that judges and has us immersed in some sort of role play, with a script that only He knows. And that what God is, is somehow dependent on what religions say that He is. As if a tree would change because I insist in saying that it is a chair.

In future articles I will expand on this idea because it has very interesting implications on Good and Evil, God as pure love, or the urge of living beings to live and perpetuate their species (something that scientists explain using the notion of “instinct” or “genetically programmed behaviors”), etc. But for now, let’s stick to the purpose of this article. If we accept that our purpose in life is to allow God to manifest Itself, and that in order for something to manifest itself we need contrast, then you may finally understand how can I relate this concept with Tonality.

In my humble opinion, art is communication. In fact, art provides the most holistic communication mode that humans have. Because only with art can you communicate complex messages that embed rational ideas, emotions and even abstract notions that could not be expressed only by rational means. Art that says nothing, is not art. As radical as that. This is why I like so much the term “Art Music”. There you can include all forms of music as an art manifestation: from classical music, to progressive rock, to jazz or traditional folklore. Other forms of music also communicate, but in the same way as instructions to build a table or the ingredients of a medicine also communicate. You would not equate a CVS recipe to a Shakespeare novel, even though both communicate. The same applies to Art vs. Non-Art Music.

So, let go back to our discussion on what is it about atonality that doesn’t “click”. In my opinion, the problem with atonal music is that it strips the listener from a frame of reference. There is no voltage. All notes are the same. Tonal music, for whatever historic or physical reason, has through the centuries been able to create a frame of reference. That frame allows us to perceive contrast and, as a result, there is a flow of communication between the composer and the listener. Thanks to this frame of reference, we perceive tension and repose, we assimilate, understand and feel, how a climax is constructed.

Atonal music has not been able to establish an alternate frame of reference. Its attempts have always been too rational: a piece based on a mathematical series is a good example. Music that can be subject to lengthy and complex musicological analysis, but incapable of establishing an effective communication flow with the listener.

As an interesting example of how tonal music has been able to create a universal frame of reference, I invite you to watch this video:

Postscript – A clarification

There is a vast catalogue of great atonal works written by talented and inspired composers. The major mystery of Art is that, in spite of our efforts to analyze and scrutinize masterpieces, we still cannot rationally apprehend their essence. We can dissect a Mozart sonata down to the last note and yet, no one (by natural or artificial means) has been able to create a Mozart-like piece that can stand side by side against Mozart’s greater works.

These modern composers have been able to convey their messages despite the fact that their language provides little references to hold on to. Sometimes the coherence is provided by rhythmic patterns, others by playing with micro tonality – you feel a tonal center but just for a brief period of time, or by ingenious combinations of timbres. Or, by letting their intuition and inspiration be their guide and achieve this communication by means that the composer is not even aware of.

These works are interspersed within a vast collection of atonal works, most of which are, in the best of cases, rational exercises and, in the worst, just fakes aimed at snobs.

Here are some examples of atonal music that I love:

Ligeti Etude 13: “The Devil’s Staircase”

Olivier Messiaen – Quatuor pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time)

Alberto Ginastera. Piano concerto No.1 Op. 28 (1961) Toccata concertata. (Yes, Keith Emerson also loved this one…)

Juan Bautista Plaza – Sonata for Two Pianos (good example of micro tonality. The tonal center is there, but moving constantly)

I never heard the Devil’s Staircase before, I enjoyed it very much, nor the Sonata for Two Pianos or the Quartet for the End of Time, not an easy listen but there is a haunting quality to them isn’t there and some sections come off better than others, which is a matter of taste of course. lt is by no means just a bunch of notes which is the stuff I don’t care for.

Yes, they are fabulous and inspired pieces indeed!

And I also enjoyed the philosophical section of the article greatly.

Thanks! A lot of food for thought…