Audio Program

The audio program streaming will be available after purchasing the article.

Download

The audio program downloading will be available after purchasing the article.

Welcome to the 9th edition of “Classic Choice”. Today: “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”.

In this analysis, for the first time, the appreciation of this classic will come more from a discussion of extra-musical elements, than a detailed analysis of the music per se. The main reason for this, is that what bounds the pieces together to form a conceptual album is not so much musical material, but the story.

When you opened the original vinyl edition, the inner-fold contained the plot of the conceptual album, setting the scene for the enjoyment of a series of surrealistic lyrics that have been subject to many interpretations over the last 40 years. With minor exceptions that will be highlighted later, the songs are independent from each other; however, the way in which they effectively portray the ambience evocated by the lyrics, gives the whole work a very strong coherence.

A bit of history

In order to fully appreciate “The Lamb”, it is important to understand the circumstances under which the work was written. We must situate ourselves in 1974. By the time “The Lamb” was being produced, Jethro Tull’s “A Passion Play” and Yes’ “Tales from Topographic Oceans” had been released and were subject to very negative assessment by the critics and a rather lukewarm reception by the audience. Because of these failures, and quoting Kevin Holm-Hudson from his excellent book “Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”:

Allow me a small digression: the reason why these albums were not well received had nothing to do with the fact that they were concept albums. As already explained in Passion Play’s analysis, both “Passion Play” and “Tales” had one thing in common: they were written with the intention to create a high form of art, disregarding commercial considerations. As high forms of art-music, they moved away from popular art – thus from the essence of rock. Both the critics and the public tried to understand these works from the perspective of popular music. These works, as well as may others in progressive rock, ended up in nowhere land: too complex to be considered rock, too rocky to be considered academic music.

By 1974, established bands were already sensing that changes in the music industry were soon to arrive. It was time to move on from mythological stories, fantastic tales that had little relation with ordinary every-day affairs. So, for the first time, Genesis would not talk about moonlit knights, harlequins or giant hogweeds: now it was all about a half Puerto Rican guy in New York City. Gabriel stated it very clearly:

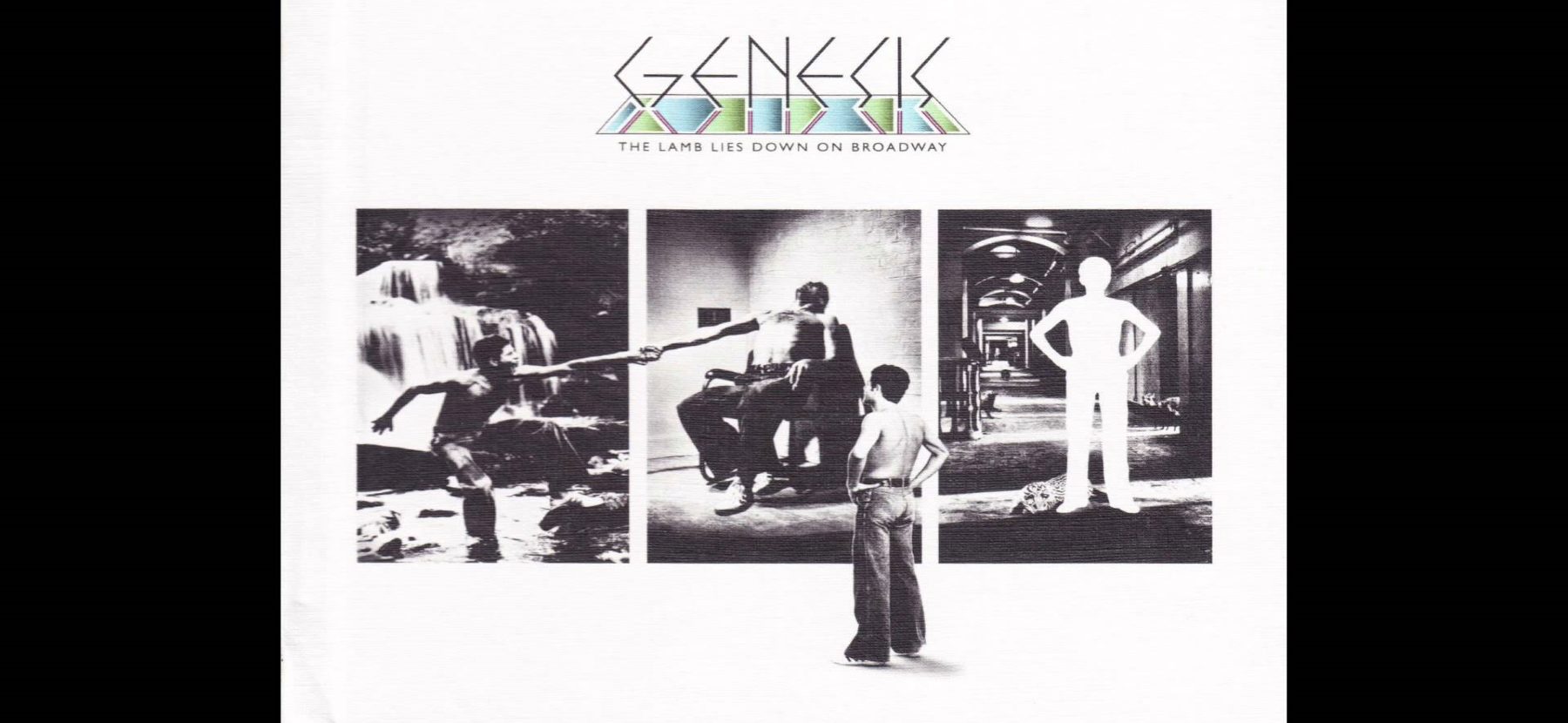

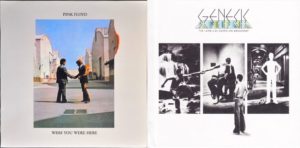

This shift was also represented in the album cover. As Holm-Hudson states:

Hipgnosis were the designers of many Pink Floyd covers, including “The Dark Side of the Moon” and “Wish You Were Here.” In fact, there are stylistic similarities between the covers of “The Lamb” and “Wish you Were Here”.

Even though, as most critics say, this album marked Genesis’ tendency towards more “mundane” matters, I have to say that what is insinuated behind this story is perhaps one of the most profound metaphysically oriented efforts by any band in the history of progressive rock.

But before we get into the interpretation of the story, let’s continue to explore the circumstances around the production of “The Lamb”.

There was a key element that determined the outcome of the album: the band was under extreme pressure from the label (Chrysalis) to release a new album. Genesis had finally made into the select group of “progressive rock super bands”, they had toured the US extensively in 1973, and their albums were selling well. But not all band members were ready to move at the same speed.

When Genesis decided to develop a concept album, they entertained a number of possibilities, including – as Rutherford suggested – an album based on “The Little Prince” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. However, they decided on the story of Rael, created by Gabriel. Traditionally, lyrics had been a group effort, but Gabriel insisted that he wanted to write all the lyrics himself:

But he could not write them at the speed required. As a result, a lot of music was written with the plot in mind, but still without the lyrics in place. Listen to this rehearsal of the song “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”. As you can hear, Gabriel was still developing the melody and babbling some words, while the instrumental arrangement was almost ready:

Genesis went off to rehearse without Gabriel, who was undergoing a difficult personal situation at the time. As described by Gabriel in Armando Gallo’s book “Genesis – I Know what I like”:

In addition, Gabriel had been contacted by William Friedkin (director of “The French Connection”, “The Exorcist”, etc.) to explore the possibility of Gabriel writing a script for a science fiction film. Banks was adamant that nothing should come before the best interest of the band. So, it was either the film or staying in the band. After a couple of weeks, Friedkin could not make a firm commitment, so Gabriel returned to the studio to complete the album. By the way, the film was eventually made – titled “Sorcerer”. It was released in 1977 with music by Tangerine Dream. It was a critical and commercial failure.

At that time, band members were extraordinarily creative and developed so much good material that, despite the label’s pressure, they decided to go for a double-album. Under such circumstances, it was a brave decision.

Gabriel’s involvement in the writing of the music was limited. Of all songs, only “Counting out Time” and “The Chamber of 32 Doors” are credited to him. So, what we had was a head-on collision between instrumental music developed based on a story, and the surrealistic world of Gabriel’s lyrics. But in the end, talent prevailed and the outcome was undoubtedly greater than the sum of its parts. It is also relevant to point out that, in spite of Gabriel’s desire to write all the lyrics, he ran out of time and asked for help. Banks and Rutherford co-authored the lyrics of “The Lights Go Down on Broadway”. The difference in lyrical style and voice (third person as opposed to first) is evident.

This extract from the book “Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” by Holm-Hudson, clearly illustrates the challenges that they had to overcome:

It is amazing that such a beautiful and well-crafted song such as “The Carpet Crawlers” was written in a rush. It is also remarkable that the integration between lyrics and music on these two songs, do not seem to be tighter than the rest, which was done in the opposite order (that is, music before the lyrics). This is yet another example of their enormous talent.

Interpretation of “The Lamb”

Throughout the years there have been many different interpretations as to what, if anything, is hidden behind the story and the lyrics. Some say that there is no hidden meaning; just a surrealistic story complemented with poetic and provocative lyrics. I have selected an interpretation included in Holm-Hudson’s book: The story of Rael can be correlated with the process of the afterlife described in the “Tibetan Book of the Dead”. I have chosen this interpretation, for several reasons:

- It is plausible, because at the time when Gabriel was writing “The Lamb” he was reading books like Carlos Castaneda’s Journey to Ixtlan, books on Zen Buddhism, The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Bright, 1998, p. 9) as well as writings by Jung. As Holm-Hudson states in his book: “Gabriel has directly linked his reading of Jung with at least “The Lamia” (Bell, 1975, p.14)”.

- Holm-Hudson cleverly identifies a musical motive that seems to represent a structural division in line with the “Bardos” described in “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”.

- When the album is approached with this fascinating interpretation, a whole new perspective is opened to the listener, allowing a renewed enjoyment of this classic.

“The Tibetan Book of The Dead” or “Bardo Thodol” might have determined the overall structure of “The Lamb”. Before looking at the story of “The Lamb” under this perspective, let me briefly explain some essential concepts from “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”. In doing so, I will also describe parallelisms with other mystical books and concepts.

In essence, the objective of “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” is to prepare oneself for the afterlife. It makes a detailed description of three different “stages” or “Bardos”, an insists on the importance of thoroughly reading the book so that the soul “understands” and is therefore “equipped” to make an efficient transit that will allow it to make the highest evolutionary leap between incarnations.

“Bardo” means “intermediate state”, “transitional state” or “in-between state”. The “Bardo Thodol” differentiates the intermediate state between physical lives into three bardos:

- The Chikhai Bardo or “bardo of the moment of death”

- The Chönyid Bardo or “bardo of the experiencing of reality”

- The Sidpa Bardo or “bardo of rebirth”

During the “Chikhai Bardo”, one is welcomed and guided to the appropriate setting for a comprehensive contemplation of the life that has just ended. During the “Chönyid Bardo” the soul experiences “visions” or “karmic illusions” that “will be heaven-like if the karma be good, or miserable and hell-like if the karma be bad” (Evans-Wentz, 1960, pp. 66-67). Finally, the “Sidpa Bardo” features karmically impelled hallucinations which eventually result in rebirth.

The ultimate goal of the Bardo is, as expressed by Jung in his “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious”:

Allow me, again a small digression: If you read my analysis of “A Passion Play Part -1” you may see the striking resemblance to what is stated in the “Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception”, particularly how the “First and Second Heavens” relate to the Chönyid Bardo and the “Third Heaven” to the Sidpa Bardo. After you finish this analysis, I invite you to revisit “A Passion Play” equating Act One with the Chikhai Bardo, Acts Two and Three with the Chönyid Bardo and Act Four with the Sidpa Bardo. I’m sure that you will agree that the similarities between Ronnie Pilgrim’s voyage and Rael’s experience are more than merely coincidental.

Ok, so let’s proceed with an interpretation of “The Lamb” based on the Bardos. According to Holm-Hudson, a possible breakdown of the album according to the three Bardos could be as follows:

Chikhai Bardo: “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”, “Fly on a Windshield”, “Broadway Melody of 1974”

Chönyid Bardo: from “Cuckoo Cocoon” to “Lilywhite Lilith”

Sidpa Bardo: from “The Waiting Room” to the end of the album.

I would make a different breakdown (more in line with the Acts of “A Passion Play”) but let’s not get too entangled with philosophical considerations. Although the exact division points maybe somewhat fuzzy, the three stages can be clearly determined. Also, keeping Holm-Hudson’s division allows me to share with you his interesting theory of what he calls “swoon music”:

As I already stated, in “The Lamb” there is virtually no continuity in the music; that is, no motives or recurring cells that give musical coherence as is the case with “A Passion Play”, but there are a few exceptions. Listen to these fragments. They appear between the first and second Bardo, and between the second and third.

Ending of “Broadway Melody of 1974” (guitar)

Last section of “Lilywhite Lilith” (mellotron)

This might be nothing more than a coincidence, given the fact that the music writing process in “The Lamb” was, for the most part, detached from the writing of the lyrics. Also, it is most probable that the other musicians were not aware of what Gabriel was reading at the time. However, it could be yet another example where inspired artists are able to unconsciously tap into a universal stream of consciousness during the creative act (for more on this you can read my article about “The Creative Process”).

Chikhai Bardo

According to both the “Tibetan Book of the Dead” and the “Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception”, physical death is followed by a period of strong disorientation. The soul (unless the person has been adequately prepared beforehand) doesn’t quite understand what is going on. Especially on sudden death, it takes the soul some time to understand that it is no longer attached to his physical body. Rael’s sudden impact with a solid cloud, that descends upon Broadway, smashing him like a “fly on a windshield”, as well as the mixed images described in “Broadway Melody of 1974” – flooded with a disconnected series of images from Broadway – is certainly a fitting description of death and the Chikhai Bardo.

Chönyid Bardo

After Rael’s shocking experience of physical death, he finds himself within a cozy cocoon, and tries to figure out what has happened. His horrible experience in The Cage, his vision of humanity in “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging”, or his past-life memories in “Back in New York City” or “Counting Out Time”, can be easily translated into the “karmic illusions” according to “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, or to the “First and Second Heavens” described in the Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception. Again, let me point out the similarities with “A Passion Play”: Rael’s experience in this Bardo is very similar to what Ronnie Pilgrim experiences in “The Memory Bank” and later in “Heaven” and “Hell”.

Many metaphysical schools, as well as religions, believe that there are highly evolved spirits that guide us, not only during the afterlife but also during our incarnated state. In the Catholic religion, for example, they are referred to as guardian angels. These guides appear both in “The Lamb” – Lilywhite Lilith and in “A Passion Play” – the angel that appears while Ronnie is wondering in limbo.

During this Bardo, the soul is presented with a number of possible choices for the starting point of its future life:

“The Chamber of 32 Doors” may represent the moment when the soul, after revisiting past lives, must decide which course his next incarnation needs to take in order to fulfill objectives or overcome particular challenges. These spirit guides play a key role in helping the soul determine its best course. Rael does not know which path to take and Lilywhite Lilith helps him find the right door. He is left in a waiting room. Rael starts its voyage back to physical life or, perhaps, liberation from the wheel of karma. He enters the last Bardo.

Sidpa Bardo

According to “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, the first entity that the soul encounters upon entering this Bardo is Yama – The Lord of Death.

This entity is better known by progressive rock fans as “The Supernatural Anesthetist”. This character in the story of “The Lamb” is to me the strongest evidence that Gabriel was influenced by the concepts of this book while writing the story. After meeting Yama, the soul experiences 6 realms of experience, one of which is the Human Realm to which most souls are drawn. What Rael experiences in “The Lamia” and “The Colony of Slippermen” can be interpreted as the deities of the Human Realm enchanting the soul with the pleasure of the senses.

The Lamia evoke the “blood-drinking” wrathful deities referred to in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, who are “only the former Peaceful Deities in changed aspect.” (Evans-Wentz, 1960, p.131)

Now, here comes the most interesting part of the story of “The Lamb”. Rael’s willingness to be castrated is, in Buddhist terms, the aim to be released from the chains of passions and desires. Rael is still not ready to abandon the wheel of karma and runs down the rapids in order to recover the plastic tube with his precious possession. He then faces the transcendental choice: a window is opened and Rael is invited to return to the Human Realm. As soon as he decides to help his brother, the window fades and his sexual organs are lost forever: the ultimate act of love, compassion and unselfishness. As he reaches the end of his journey, he is finally aware that physical existence is an illusion – Maya as the Hindus call it – and, as that moment is reached, he sees himself in the face of his brother John. Let Gabriel himself end the story:

Rael, has finally reached satori – enlightenment.

Holm-Hudson points out that “brother John appears as a symbol of spiritual aspiration for Rael” (Holm-Hudson, 2008, p. 72). I propose to you the following interpretation: John represents Rael’s Higher-Self. When trapped in “The Cage”, John’s disappearance might be an invitation to follow him. When Rael follows his higher-self, the hallucination stops. Later, in “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging”, he sees his brother John with a “9” stamped on his forehead which represents Divine perfection (3×3). Again, John’s appearance seems to drive Rael away from this second hallucination. It is John who saves Rael from the Colony of Slippermen and, in the key moment of Rael’s voyage through the afterlife, when the window to return is opened, it is again John who helps him decide. At the end of the story, Rael regains full contact with his higher-self and is thus liberated from the karmic cycle.

The Music of “The Lamb”

From a structural point of view, there is no overarching scheme to bind the piece into a coherent musical entity. “The Lamb” is comprised of a collection of songs that share little thematic relation. In addition to the “swoon” music referred to in the previous section, the only other instances of related songs are “The Light Dies Down on Broadway” which is a double reprise with material from the opening track and “The Lamia” and there is also a reprise from “Broadway Melody of 1974” in Lilywhite Lilith. We will discuss these later.

Citing Holm-Hudson:

Some musicologists like Allan Moore have suggested that the use of certain “harmonic fingerprints” are used to provide musical unity to the album. However, I think this is more due to the fact that most of the music was written by Banks, thus, these harmonic progressions have more to do with his style of writing, than to a deliberate attempt to provide unity.

However, this in no way implies that the music is not worthy of attention. In spite of being a collection of musically unrelated songs, their ability to convey the images suggested by the lyrics and the overall plot is remarkable. The unity and cohesiveness of the work as a conceptual album, was achieved despite the challenges that band members had to confront at the time of writing and recording the work.

Much of the analysis that follows, is based on an excellent chapter called “’Counting out time’; The Lamb, song by song” from the book “Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” by Kevin Helm-Hudson. As I’ve done with previous analyses, I have selected the elements that provide a better understanding of the work, and excluded the more technical discussions.

Because of the simple expanded song format of most of the songs, I will not go into a structural analysis of each song. Doing so would not provide much in terms of enhancing the listening pleasure of these pieces. Instead, let’s discuss some interesting features in selected songs.

One interesting characteristic of “The Lamb” is that it is full of references to songs of the 60’s. Let’s look at them:

At the end of “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”, as the song is fading, we can hear a musical and lyrical quote from the 1963 Drifters hit “On Broadway”

“Broadway Melody of 1974” ends with an intertextual song reference: “Needles and Pins” written by Sonny Bono and Jack Nitzsche, a song by The Searchers from their album “Needles and Pins” that was a UK #1 hit in 1964.

During “The Cage”, there is a clear reference to the famous song “Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head” from Burt Bacharach and Hal David, although at a much faster pace:

Finally, the closing line of the lyrics in the album on the song “It”: “It’s only knock and knowall, but I like it” refers to the Rolling Stones’ 1974 hit “It’s Only Rock and Roll”

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

Written in a simple song format (AABA + a fading out Coda) and in straight 4/4 beat, this song is nevertheless full of creativity and strength. If you have followed all previous analysis up to date, you should be able to identify each section yourself. Feel free to give it a shot and post it in the comments section. The fading Coda is where the hit from The Drifters in quoted.

Upon exiting the subway, Rael describes what he sees in the streets of New York City, just before being thrown to the afterlife by the sudden blow of death.

Fly on a Windshield / Broadway Melody of 1974

Over a beautiful and dreamy guitar, complemented by voice mellotrons and electric piano, Rael describes

If you want to read the rest of the article, you need to buy it:

Resources

This analysis would not have been possible without the solid foundation laid by Holm-Hudson’s excellent book ”Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”. Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series. First Edition. It can be purchased here.

Genesis photographs were scanned from my personal copy of Armando Gallo’s book “Genesis I Know What I Like” D.I.Y Books, 1980. It can be purchased here.

The background music used is:

- The piece “Dionisio de Magnesia” by the Spanish band Tricantropus, from their album “El Sueño de Arsione”

- The piece “L’etau Familial” by the French band Yang, from their album “Machines”

- The piece “Hydraulic Fracas” by the USA band Zhongyu, from their album “”Zhongyu” Is Chinese For “Finally””

- The piece “Structure 5” by the Spanish band Kotebel, from their album “Structures”

- The piece “Sleepwalking the Dog” by the USA band Zhongyu, from their album “”Zhongyu” Is Chinese For “Finally””

- The piece “9/8 Variations” by the French band Yang, from their album “The Failure of Words”

- The piece “Zodiac” by the USA band Ut Gret, from their album “Ancestor’s Tale”

- The piece “De la Mélancolie à la révolte” by the French band Yang, from their album “Machines”

- The piece “3éme Messs” by the French band Yang, from their album “Machines”

It is extremely difficult to find The Lamb’s story in the Internet. Of the several links referred to in Holm-Hudson’s book, the only one still active (at the time of writing this article in October 2017) is:

http://www.ferhiga.com/progre/notas/notas-genesis-tlldob-ingles.htm

“Lilywhite Lilith” was a reworking of an early Genesis song called “The Light” (Bowler and Dray, 1993, p. 94). That early song provided the guitar riff and the verse melody of “Lilywhite Lilith” (Russel, 2004, p. 203). Banks remembers:

The “little triplet section” to which Bank refers also wound up recycled for “The Lamb” as “The Raven” section of “The Colony of Slippermen.” (Holm-Hudson, 1980 , p. 83).

This is the only recording of “The Light” known to exist, from a performance at the La Ferme V club in Belgium, on 1971:

There are no high-quality video recordings of “The Lamb” tour. This is one of the better ones that you can find in YouTube:

The entire “Lamb” performance at “Shrine Auditorium” in Los Angeles on January 24th 1975, is included in the Genesis Archive 1967-75 Box Set.

You can listen to this performance in public YouTube links but if you like it, please purchase the box set!