Audio Program

Download

We remind you that the audio fragments embedded in the text are to be used when reading the article without listening to the audio program. All these examples are included in the audio program.

Welcome to the fourth edition of the Classic of the Month. Today we will submerge in the world of “Starless” by King Crimson.

As I mentioned in last month’s article Progressive Rock – a Misleading Tag one of the most prominent characteristics of this genre is, as a neo-baroque expression, the development of thematic material aimed at building one or several climaxes throughout the piece. Other 2 characteristics of neo-baroque that represent this genre very well and are key to the construction of “Starless” are:

- the aesthetic of repetition and variation

- a desire to evoke states of transcendence

“Starless” is a perfect example of how the use of repetition and variation, as well as harmonic resources, can be used to gradually build a series of climaxes. The obsessive repetition of single notes is hypnotic and helps to create a unique environment that naturally leads to the climaxes that have made this song an all-time classic.

Starless uses a couple of harmonic resources that are very common in progressive rock (and in classical music as well): harmonic pedals and a couple of cadences known as “deceptive” and “suspended”. But before we describe how these resources are used in the piece, we need first to make a crash course in basic principles of tonality.

Tonality and “expectation” go hand in hand. In the discussion that will follow, when I talk about “attraction” and “intensity of the attraction” what I mean is what our mind has been trained to “expect” and how “strong” this expectation is.

To describe tonality without having basic notions of music theory is tricky but let’s give it a shot. In order to achieve this, let’s think of notes as magnets with different intensities, and even different polarities. In my article Tonality and the Purpose of Life I explained that the way tonality is perceived is by creating a hierarchy of notes. So, once we perceive a tonal center, notes immediately have ranks assigned. Some are heavily attracted to the tonal center, others are attracted but to a lesser degree and this allows them to be used as pivotal points to modulate to other tonalities. And others are not attracted, quite the opposite, their polarity is reversed and tend to move away from the tonic. These notes, and the chords (that is, 3 or more notes played simultaneously) built around them are used to create dissonant chords.

In that article I also argue that the reason why tonal music has been so strongly engrained in our culture is because it has been able to create a frame of reference. In other words, we have been trained to “expect” an outcome when we hear a series of chords. Even if we have no music training, if we listen to this series of chords we automatically expect the outcome:

In tonal music, a cadence is a sequence of chords that concludes a musical phrase. When we hear a series of chords and expect the next one, what is happening in the background is that one of many different cadences is in action. These cadences have been used for centuries and are at the core of this “aural conditioning” that has built the tonal frame of reference in the western culture. When we hear the chord that we are expecting, probably a cadence known as “perfect” has occurred. What I played in the previous example, was a perfect cadence.

If, on the other hand, instead of the chord that you are expecting you hear another one, then you probably heard one of several cadences known as “interrupted” or “deceptive” cadences. Some “deceptive” cadences use a chord known as “Neapolitan 6th” for this purpose. Let me give you an example. First let’s listen to a perfect cadence:

In this case, I start in F, and play a couple of chords that lead me back to F, where I started. Straightforward and predictable.

Now let’s change this perfect cadence into a “deceptive” one, using the Neapolitan 6th chord. This chord is an example of many that can be used to move the tonal center. I will play the same F chord again and the first of the two chords used in the previous example. But then, at the third chord (0:03) you will hear the Neapolitan 6th. I will use it to move the tonal center. After playing two more chords, I will finish in B flat instead of F. So, I used the Neapolitan 6th chord to build a cadence that allowed me to modulate from one tone to another.

Let’s listen to this example by Camel, who uses the “Neapolitan 6th” in their suite “Harbour of Tears”:

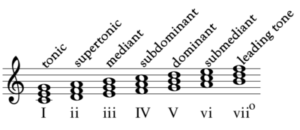

Before moving on, let’s go a little further in the explanation of tonality. When we define a tonal center, the chord that sits on the tonal center is called “tonic”. The other chords are assigned ranks, whose names are suggestive of how closely related they are to the tonic. It may or may not explain why humans have adopted the tonal structure that we have, but the fact is that the second most important chord, in terms of its magnetic attraction to the tonic, is called “Dominant Chord” or “V”, which happens to match the first harmonic tone that appears in the harmonic series after the fundamental tone itself (and its octave). The magnetic attraction between the dominant and tonic is evident for all westerners.

As you will see, the note B, that sits next to the tonic: C, has an irresistible temptation to move towards the tonic.

This note is very important in the dominant chord because it can determine the 2 modes used extensively in Western music: major and minor.

Other chords have different rankings depending on how strongly they lead back to the tonic. The names are:

As I said, we have been conditioned to expect how these chords relate to each other, even with no music training.

One of the most famous sequence of chords is the one defined in Pachelbel’s canon in D Major. Most of you have probably seen this video where the comedian Rob Paravonian shows how this sequence of chords have been used and abused in every music genre. For those reading the article, here it is in case you have never seen it.

Playing with these harmonic expectations is the basis for the creation of tension and distension in tonal music. There are innumerable ways to disrupt cadences and to modulate from one tonal center to another. They require a good understanding of harmony and are far beyond the scope of this simple introduction. However, there is a resource that is very easy to construct and maybe that is why it has been used so extensively in progressive rock: harmonic pedals.

A very important note in any chord is the first, or lowest, because it helps identify the tonal center. In a simple chord, here it is:

To see how important it is, let me play the same tonic – dominant chord, playing the bass at a higher volume,

Now listen to what happens if I invert the order of the bass note:

This harmonic resource is used very frequently by prog composers like Tony Banks.

A harmonic pedal is built by keeping the bass note constant while changing the harmony. Examples in progressive rock are countless. So, let me give you an example in classical music. This is how it is used by Rachmaninov in his Piano Concerto No. 2 Opus 18 in C minor. The piece starts with a harmonic pedal but not in the tonic but instead the subdominant: F. Before introducing the main theme, it moves to the dominant (G) and ends in C, the tonic, and the main theme is introduced. Listen to the first 30 seconds in this interpretation by Anna Fedorova and the North West German Philharmonic conducted by Martin Panteleev:

The coda of the second movement is one of the most beautiful passages that I have ever listened to. The harmonic pedal moves effortlessly until it is kept steady in the end. For those of you reading the article and watching the video examples, notice at 00:37 that the double bass players are playing the E note in the air. This is the lowest pitch of the instrument. Their left hand is resting in the body of the instrument. This harmonic pedal is kept until the end of the movement only interrupting the pedal for a moment, when the soloist plays the dominant (B) to finish the piece in the tonic: E.

The following is a good example of both resources – harmonic pedal and deceptive cadence, used in conjunction.

This is the coda of Triptych – Noon Mist published in issue #2 of Phaedrus. Notice that the bass keeps a constant note “A” – the harmonic pedal. It runs through three complete cycles; the third chord prepares a return to the tonic but the fourth chord breaks the cycle – a deceptive cadence. The fourth and final time, the harmony finally resolves but in “A” Major instead of “a” minor. Let’s listen to it:

Sometimes the harmonic pedal expands, forming a chord that remains static, building tension and a hypnotic atmosphere until the chord finally resolves. Pink Floyd use this resource masterfully in “Shine on You Crazy Diamond”. At the beginning of the piece, the pedal is kept for more than 2 minutes (I mean in the original piece, not this fragment) before resolving (1:11). For 30 seconds the tonal center moves, and in 2:13 another static pedal section starts, beneath the famous 4-note motif played by the guitar. Notice the very different character of these 4 notes when, at 3:18 it finally resolves:

We are now prepared to take on the analysis of Starless.

In Starless, another type of cadence called “suspended” is used very effectively. In this case, what happens is that you are not thrown off in another direction like in the case of a “deceptive” cadence but rather almost come to conclusion, but not quite. You are left suspended, very close to the real resolution, but not there yet.

Let me play for you the opening measures so you can easily identify where the suspended cadence is.

The cadence is suspended by keeping the harmonic pedal; in other words, by not moving the bass to the tonic. Even though the section is in G minor, the bass note is playing a D and keeps that note creating a harmonic pedal that doesn’t resolve as one would expect. For those with music knowledge, you will see that the D in the bass creates the second inversion of the G minor chord:

The natural cadence would be this:

Those of you who know the piece well, will have already detected what I am about to say: this cadence is not resolved until the very end of the piece. Let’s listen to all the sections where this cadence appears:

And in the end of the piece (between 00:12 and 00:13 in the example) it finally resolves:

Let’s go through the piece analyzing its structure. Eric Tamm in his article “From Crimson King to Crafty Master” states that Starless is in a loose Sonata form. I disagree because in my opinion the only aspect in common with a Sonata form is that the piece has 2 themes and a long development section. It is true, as he claims, that modern sonatas don’t follow the format following the strict classical rules; for example, in the 20th century, it is common to present the 2 themes on unrelated tonalities, however, the fundamental characteristic of a Sonata form is the development of the themes presented during the exposition. This doesn’t happen in Starless, aside from the fact that the horn briefly presents the vocal theme in the middle of the “C” development. But let’s discuss this as we move through the piece. In my opinion, the structure is:

A (twice) – B (twice with a short interlude) – A (once) – B (once) – C (instrumental – independent development with an interlude that re-exposes B) – A’

The C section leads to the recapitulation of “A” labelled A’ because, as described earlier, the cadence is finally resolved.

Section A

Under a straight 4/4 rhythm, the section presents 2 themes, the first one is based on mellotron strings and the second introduces a guitar based melody. The second time, the guitar moves up an octave when playing the second theme.

Section B

This is the only vocal section of the piece. It has a single theme, backed by embellishments provided by the saxophone. As in section A, it is also in G minor. These are the lyrics:

Sundown dazzling day

Gold through my eyes

But my eyes turned within

Only see

Starless and bible black

Ice blue silver sky

Fades into grey

To a grey hope that omens to be

Starless and bible black

Old friend charity

Cruel twisted smile

And the smile signals emptiness

For me

Starless and bible black

It would appear that these lyrics present a reflection on the fact that reality is dependent on our interpretation of what we perceive. The scene depicted can be interpreted in opposite ways.

The lyrics provide three interpretations of what is being perceived, that would likely come from a person with a profound depression:

In the middle of a “dazzling dusk” with “gold pouring through my eyes”, my eyes turn within and I only see “Starless and Bible Black”.

As dusk approaches (Ice blue silver sky, fades into grey), the shades of grey are interpreted as an omen of a dark and ominous future.

The smile of a friend is perceived as charity, the smile turns into a twisted and cruel grin. His smile transforms into emptiness within.

But, from a different perspective, the scene could have been: On a bright afternoon, oblique sunbeams project a special light, as one sees a good friend approaching us while he smiles. Soon the sun disappears giving rise to a beautiful landscape of colors that slowly turn into grey.

Of course, the music of “Starless” would not have provided a good setting for this second interpretation…

Notice that the main vocal theme is repeated twice. The first time, a deceptive cadence in the phrase “Bible Black” is used to prepare the repetition, the second time, it resolves. When the vocal theme is presented again, the deceptive cadence reappears in 0:26, moving the tonality to C (that is, modulating to C) and setting the scene for the long instrumental section.

Section C

The first thing to notice, is that C section is based on a 13/8 metric. I will put a few measures so you can try to count them. The way to know when the measure ends, is when the bass figure starts again.

In case you couldn’t identify the beats, let me count them for you:

The “C” section is in C minor, so the tonal center is around C. Let’s see how tension is built in this section.

The bass pattern presents the main resource used in Starless to create tension: After playing the tonic “C”, it sits for a while on F# before moving to G (the dominant) and then back to C through E flat. The interval between C and F# is made up of three whole tones and is usually referred to as a “Tritone”. The Tritone is traditionally known in music as the “diabolus in musica” (The Devil in music). By the way, the Tritone is used extensively in progressive rock. This single note, F#, immediately starts to build tension in this section of Starless.

The first repetitive note in the guitar is a G, which is the dominant of C and therefore builds a very stable and consonant chord.

The bass moves to F, the subdominant of C, which is a standard harmonic sequence, but keeps the same pattern, this time creating the Tritone between F and B.

While this is happening in the bass, the guitar picks a note none other than F#; that is, the same Tritone from C introduced previously by the bass. So, we are now confronted with a tonal ambiguity: Are we still in C or did we move to F? So, even if you have absolutely no training in music, as a listener, you already start to feel uneasy in your chair, just a few seconds into section C:

The guitar goes back to G, and the bass back to its pattern on C. So, everything would point back to stability if it weren’t for the stringent B, slightly out of tune moving down towards B flat, and then played an octave higher but in B flat, also a bit out of tune and moving up towards B. In the context of the tritone played by the bass, this ambiguous note that moves between B and B flat works as a catapult and throws you right into a starless void. And we’ re are only 35 seconds into section C … Remember that, in addition to this, we are still moving under a 13/8 metric.

Finally, both bass and guitar play the G note (the dominant of C), and the tension built is relaxed because we move back to C, as we are all expecting, in order to start the cycle once again. Notice that this passage is on 4/4. So, in every cycle, when we reach G, the metric changes to 4 beats and back to 13 when the next cycle begins.

On the second cycle, you hear a couple of wood blocks. They are played in 4/8 not in 13/8. Therefore, they start to shift as the cycle progresses. Try to count them. Also, the guitar, always in obsessive single note repetition, starts moving up the C scale until it reaches B. In the tonality of C, B is the note most heavily attracted to C, so when the bass moves to C, we are expecting the guitar to do the same, but instead, it stays on B. This is the beginning of the section that builds the famous Starless climax:

On the third cycle, the drums finally come into play, as the guitar continues to obsessively play B instead of C. Notice that, at the end of the previous cycle, the wood blocks play a few irregular beats and when the drum pattern settles, the wood blocks go in patterns of 3, instead of 4.

Bruford masterfully starts building tension as the guitar ascends: C, D, E flat, F, F# while gradually transforming from a clean to a distorted sound, and we reach a first climax plateau when in the fourth cycle, the guitar reaches G (1:10 in the example), but gliding back and forth between F# (the tritone) and G. In this fourth cycle, the drum is at full force, with clever percussion embellishments. The guitar again goes back to the Tritone, as in the beginning of the section, but an octave higher and keeping the distortion as opposed to the clean sound that appeared in the beginning of section C. Let’s listen to the third and fourth cycles:

We reach an interlude in 4/4, where two syncopated guitars support the lead guitar as it ascends. For those of you with more music knowledge, notice that additional tension is achieved by using a whole-tone scale as it moves up an octave from “G” to “G”.

We reach the second climax plateau when the sax improvisation starts, while the rhythm returns to 13 beats, but doubling the speed using sixteenth notes. The improvisation lasts for 2 full cycles. Notice that between the 2 cycles, the metric goes to 4/4, letting a bit of breathing space before returning to the 13/16 metric. The guitar chords signal the beginning of each measure, both 13/16 and 4/4:

Another interlude appears, based on an instrumental version of section “B” with an oboe and a cornet instead of the voice.

We finally reach the next to last climax plateau and the longest one: for two full cycles, doubling the speed of the initial section C, the guitar stays obsessively moving from G to F# (the tritone). Bass and drums at full force, and a second rhythm guitar further contributes to this sonic tsunami.

Section A’

The last cycle leads to the re-exposition of theme “A”, this time finally resolving the cadence, as we saw previously. The moment when this cadence is resolved, at 0:33, represents to me the final and most intense climax of the piece:

Resources

All “Starless” musical examples have been taken from my personal copy of Red, based on the original master published in 1974.

The Neapolitan 6th example is taken from the suite “Harbor of Tears” included in the live album double CD “Coming of Age” by Camel.

The Pink Floyd example is an extract of “Shine on you Crazy Diamond”, included in the album “Wish you were Here”.

Background music

I use a couple of songs from the album “Elixir” by “Varga Janos Project”:

- Eldorado

- Rozsak A Folyon

And also the piece “Tango” from the album “Beau Soleil” by the band “Philharmonie”.

Here’s the entire Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 2 Opus 18 in C minor interpreted by Anna Fedorova and the North West German Philharmonic conducted by Martin Panteleev:

There are many cover versions of this piece. My favorite is this live version by the Hungarian band “After Crying” featuring John Wetton.

There are countless versions of Starless in the web, so I chose the latest incarnation of King Crimson which, at the time of writing of this article, is the “Radical Action to Unseat the Hold of Monkey Mind” (2015/2016)

I have never heard of Neopolitan 6th and 13/8 I did not realize it was in that before, thanks a lot!

Very well done, a fascinating and insightful article on one of my favourite songs!

Another great, although massively de-progged cover version of this true classic is by The Unthanks on their “Last” album. Credits for this arrangement go to their member and “musical director” Adrian McNally…

Thanks for the tip! Will have to check out this de-progged version. Should be interesting!