Audio Program

Download

Welcome to the 9th edition of “Classic Choice”. Today: “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”.

In this analysis, for the first time, the appreciation of this classic will come more from a discussion of extra-musical elements, than a detailed analysis of the music per se. The main reason for this, is that what bounds the pieces together to form a conceptual album is not so much musical material, but the story.

When you opened the original vinyl edition, the inner-fold contained the plot of the conceptual album, setting the scene for the enjoyment of a series of surrealistic lyrics that have been subject to many interpretations over the last 40 years. With minor exceptions that will be highlighted later, the songs are independent from each other; however, the way in which they effectively portray the ambience evocated by the lyrics, gives the whole work a very strong coherence.

A bit of history

In order to fully appreciate “The Lamb”, it is important to understand the circumstances under which the work was written. We must situate ourselves in 1974. By the time “The Lamb” was being produced, Jethro Tull’s “A Passion Play” and Yes’ “Tales from Topographic Oceans” had been released and were subject to very negative assessment by the critics and a rather lukewarm reception by the audience. Because of these failures, and quoting Kevin Holm-Hudson from his excellent book “Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”:

Allow me a small digression: the reason why these albums were not well received had nothing to do with the fact that they were concept albums. As already explained in Passion Play’s analysis, both “Passion Play” and “Tales” had one thing in common: they were written with the intention to create a high form of art, disregarding commercial considerations. As high forms of art-music, they moved away from popular art – thus from the essence of rock. Both the critics and the public tried to understand these works from the perspective of popular music. These works, as well as may others in progressive rock, ended up in nowhere land: too complex to be considered rock, too rocky to be considered academic music.

By 1974, established bands were already sensing that changes in the music industry were soon to arrive. It was time to move on from mythological stories, fantastic tales that had little relation with ordinary every-day affairs. So, for the first time, Genesis would not talk about moonlit knights, harlequins or giant hogweeds: now it was all about a half Puerto Rican guy in New York City. Gabriel stated it very clearly:

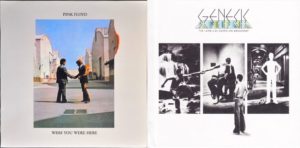

This shift was also represented in the album cover. As Holm-Hudson states:

Hipgnosis were the designers of many Pink Floyd covers, including “The Dark Side of the Moon” and “Wish You Were Here.” In fact, there are stylistic similarities between the covers of “The Lamb” and “Wish you Were Here”.

Even though, as most critics say, this album marked Genesis’ tendency towards more “mundane” matters, I have to say that what is insinuated behind this story is perhaps one of the most profound metaphysically oriented efforts by any band in the history of progressive rock.

But before we get into the interpretation of the story, let’s continue to explore the circumstances around the production of “The Lamb”.

There was a key element that determined the outcome of the album: the band was under extreme pressure from the label (Chrysalis) to release a new album. Genesis had finally made into the select group of “progressive rock super bands”, they had toured the US extensively in 1973, and their albums were selling well. But not all band members were ready to move at the same speed.

When Genesis decided to develop a concept album, they entertained a number of possibilities, including – as Rutherford suggested – an album based on “The Little Prince” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. However, they decided on the story of Rael, created by Gabriel. Traditionally, lyrics had been a group effort, but Gabriel insisted that he wanted to write all the lyrics himself:

But he could not write them at the speed required. As a result, a lot of music was written with the plot in mind, but still without the lyrics in place. Listen to this rehearsal of the song “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”. As you can hear, Gabriel was still developing the melody and babbling some words, while the instrumental arrangement was almost ready:

Genesis went off to rehearse without Gabriel, who was undergoing a difficult personal situation at the time. As described by Gabriel in Armando Gallo’s book “Genesis – I Know what I like”:

In addition, Gabriel had been contacted by William Friedkin (director of “The French Connection”, “The Exorcist”, etc.) to explore the possibility of Gabriel writing a script for a science fiction film. Banks was adamant that nothing should come before the best interest of the band. So, it was either the film or staying in the band. After a couple of weeks, Friedkin could not make a firm commitment, so Gabriel returned to the studio to complete the album. By the way, the film was eventually made – titled “Sorcerer”. It was released in 1977 with music by Tangerine Dream. It was a critical and commercial failure.

At that time, band members were extraordinarily creative and developed so much good material that, despite the label’s pressure, they decided to go for a double-album. Under such circumstances, it was a brave decision.

Gabriel’s involvement in the writing of the music was limited. Of all songs, only “Counting out Time” and “The Chamber of 32 Doors” are credited to him. So, what we had was a head-on collision between instrumental music developed based on a story, and the surrealistic world of Gabriel’s lyrics. But in the end, talent prevailed and the outcome was undoubtedly greater than the sum of its parts. It is also relevant to point out that, in spite of Gabriel’s desire to write all the lyrics, he ran out of time and asked for help. Banks and Rutherford co-authored the lyrics of “The Lights Go Down on Broadway”. The difference in lyrical style and voice (third person as opposed to first) is evident.

This extract from the book “Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” by Holm-Hudson, clearly illustrates the challenges that they had to overcome:

It is amazing that such a beautiful and well-crafted song such as “The Carpet Crawlers” was written in a rush. It is also remarkable that the integration between lyrics and music on these two songs, do not seem to be tighter than the rest, which was done in the opposite order (that is, music before the lyrics). This is yet another example of their enormous talent.

Interpretation of “The Lamb”

Throughout the years there have been many different interpretations as to what, if anything, is hidden behind the story and the lyrics. Some say that there is no hidden meaning; just a surrealistic story complemented with poetic and provocative lyrics. I have selected an interpretation included in Holm-Hudson’s book: The story of Rael can be correlated with the process of the afterlife described in the “Tibetan Book of the Dead”. I have chosen this interpretation, for several reasons:

- It is plausible, because at the time when Gabriel was writing “The Lamb” he was reading books like Carlos Castaneda’s Journey to Ixtlan, books on Zen Buddhism, The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Bright, 1998, p. 9) as well as writings by Jung. As Holm-Hudson states in his book: “Gabriel has directly linked his reading of Jung with at least “The Lamia” (Bell, 1975, p.14)”.

- Holm-Hudson cleverly identifies a musical motive that seems to represent a structural division in line with the “Bardos” described in “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”.

- When the album is approached with this fascinating interpretation, a whole new perspective is opened to the listener, allowing a renewed enjoyment of this classic.

“The Tibetan Book of The Dead” or “Bardo Thodol” might have determined the overall structure of “The Lamb”. Before looking at the story of “The Lamb” under this perspective, let me briefly explain some essential concepts from “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”. In doing so, I will also describe parallelisms with other mystical books and concepts.

In essence, the objective of “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” is to prepare oneself for the afterlife. It makes a detailed description of three different “stages” or “Bardos”, an insists on the importance of thoroughly reading the book so that the soul “understands” and is therefore “equipped” to make an efficient transit that will allow it to make the highest evolutionary leap between incarnations.

“Bardo” means “intermediate state”, “transitional state” or “in-between state”. The “Bardo Thodol” differentiates the intermediate state between physical lives into three bardos:

- The Chikhai Bardo or “bardo of the moment of death”

- The Chönyid Bardo or “bardo of the experiencing of reality”

- The Sidpa Bardo or “bardo of rebirth”

During the “Chikhai Bardo”, one is welcomed and guided to the appropriate setting for a comprehensive contemplation of the life that has just ended. During the “Chönyid Bardo” the soul experiences “visions” or “karmic illusions” that “will be heaven-like if the karma be good, or miserable and hell-like if the karma be bad” (Evans-Wentz, 1960, pp. 66-67). Finally, the “Sidpa Bardo” features karmically impelled hallucinations which eventually result in rebirth.

The ultimate goal of the Bardo is, as expressed by Jung in his “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious”:

Allow me, again a small digression: If you read my analysis of “A Passion Play Part -1” you may see the striking resemblance to what is stated in the “Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception”, particularly how the “First and Second Heavens” relate to the Chönyid Bardo and the “Third Heaven” to the Sidpa Bardo. After you finish this analysis, I invite you to revisit “A Passion Play” equating Act One with the Chikhai Bardo, Acts Two and Three with the Chönyid Bardo and Act Four with the Sidpa Bardo. I’m sure that you will agree that the similarities between Ronnie Pilgrim’s voyage and Rael’s experience are more than merely coincidental.

Ok, so let’s proceed with an interpretation of “The Lamb” based on the Bardos. According to Holm-Hudson, a possible breakdown of the album according to the three Bardos could be as follows:

Chikhai Bardo: “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”, “Fly on a Windshield”, “Broadway Melody of 1974”

Chönyid Bardo: from “Cuckoo Cocoon” to “Lilywhite Lilith”

Sidpa Bardo: from “The Waiting Room” to the end of the album.

I would make a different breakdown (more in line with the Acts of “A Passion Play”) but let’s not get too entangled with philosophical considerations. Although the exact division points maybe somewhat fuzzy, the three stages can be clearly determined. Also, keeping Holm-Hudson’s division allows me to share with you his interesting theory of what he calls “swoon music”:

As I already stated, in “The Lamb” there is virtually no continuity in the music; that is, no motives or recurring cells that give musical coherence as is the case with “A Passion Play”, but there are a few exceptions. Listen to these fragments. They appear between the first and second Bardo, and between the second and third.

Ending of “Broadway Melody of 1974” (guitar)

Last section of “Lilywhite Lilith” (mellotron)

This might be nothing more than a coincidence, given the fact that the music writing process in “The Lamb” was, for the most part, detached from the writing of the lyrics. Also, it is most probable that the other musicians were not aware of what Gabriel was reading at the time. However, it could be yet another example where inspired artists are able to unconsciously tap into a universal stream of consciousness during the creative act (for more on this you can read my article about “The Creative Process”).

Chikhai Bardo

According to both the “Tibetan Book of the Dead” and the “Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception”, physical death is followed by a period of strong disorientation. The soul (unless the person has been adequately prepared beforehand) doesn’t quite understand what is going on. Especially on sudden death, it takes the soul some time to understand that it is no longer attached to his physical body. Rael’s sudden impact with a solid cloud, that descends upon Broadway, smashing him like a “fly on a windshield”, as well as the mixed images described in “Broadway Melody of 1974” – flooded with a disconnected series of images from Broadway – is certainly a fitting description of death and the Chikhai Bardo.

Chönyid Bardo

After Rael’s shocking experience of physical death, he finds himself within a cozy cocoon, and tries to figure out what has happened. His horrible experience in The Cage, his vision of humanity in “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging”, or his past-life memories in “Back in New York City” or “Counting Out Time”, can be easily translated into the “karmic illusions” according to “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, or to the “First and Second Heavens” described in the Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception. Again, let me point out the similarities with “A Passion Play”: Rael’s experience in this Bardo is very similar to what Ronnie Pilgrim experiences in “The Memory Bank” and later in “Heaven” and “Hell”.

Many metaphysical schools, as well as religions, believe that there are highly evolved spirits that guide us, not only during the afterlife but also during our incarnated state. In the Catholic religion, for example, they are referred to as guardian angels. These guides appear both in “The Lamb” – Lilywhite Lilith and in “A Passion Play” – the angel that appears while Ronnie is wondering in limbo.

During this Bardo, the soul is presented with a number of possible choices for the starting point of its future life:

“The Chamber of 32 Doors” may represent the moment when the soul, after revisiting past lives, must decide which course his next incarnation needs to take in order to fulfill objectives or overcome particular challenges. These spirit guides play a key role in helping the soul determine its best course. Rael does not know which path to take and Lilywhite Lilith helps him find the right door. He is left in a waiting room. Rael starts its voyage back to physical life or, perhaps, liberation from the wheel of karma. He enters the last Bardo.

Sidpa Bardo

According to “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, the first entity that the soul encounters upon entering this Bardo is Yama – The Lord of Death.

This entity is better known by progressive rock fans as “The Supernatural Anesthetist”. This character in the story of “The Lamb” is to me the strongest evidence that Gabriel was influenced by the concepts of this book while writing the story. After meeting Yama, the soul experiences 6 realms of experience, one of which is the Human Realm to which most souls are drawn. What Rael experiences in “The Lamia” and “The Colony of Slippermen” can be interpreted as the deities of the Human Realm enchanting the soul with the pleasure of the senses.

The Lamia evoke the “blood-drinking” wrathful deities referred to in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, who are “only the former Peaceful Deities in changed aspect.” (Evans-Wentz, 1960, p.131)

Now, here comes the most interesting part of the story of “The Lamb”. Rael’s willingness to be castrated is, in Buddhist terms, the aim to be released from the chains of passions and desires. Rael is still not ready to abandon the wheel of karma and runs down the rapids in order to recover the plastic tube with his precious possession. He then faces the transcendental choice: a window is opened and Rael is invited to return to the Human Realm. As soon as he decides to help his brother, the window fades and his sexual organs are lost forever: the ultimate act of love, compassion and unselfishness. As he reaches the end of his journey, he is finally aware that physical existence is an illusion – Maya as the Hindus call it – and, as that moment is reached, he sees himself in the face of his brother John. Let Gabriel himself end the story:

Rael, has finally reached satori – enlightenment.

Holm-Hudson points out that “brother John appears as a symbol of spiritual aspiration for Rael” (Holm-Hudson, 2008, p. 72). I propose to you the following interpretation: John represents Rael’s Higher-Self. When trapped in “The Cage”, John’s disappearance might be an invitation to follow him. When Rael follows his higher-self, the hallucination stops. Later, in “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging”, he sees his brother John with a “9” stamped on his forehead which represents Divine perfection (3×3). Again, John’s appearance seems to drive Rael away from this second hallucination. It is John who saves Rael from the Colony of Slippermen and, in the key moment of Rael’s voyage through the afterlife, when the window to return is opened, it is again John who helps him decide. At the end of the story, Rael regains full contact with his higher-self and is thus liberated from the karmic cycle.

The Music of “The Lamb”

From a structural point of view, there is no overarching scheme to bind the piece into a coherent musical entity. “The Lamb” is comprised of a collection of songs that share little thematic relation. In addition to the “swoon” music referred to in the previous section, the only other instances of related songs are “The Light Dies Down on Broadway” which is a double reprise with material from the opening track and “The Lamia” and there is also a reprise from “Broadway Melody of 1974” in Lilywhite Lilith. We will discuss these later.

Citing Holm-Hudson:

Some musicologists like Allan Moore have suggested that the use of certain “harmonic fingerprints” are used to provide musical unity to the album. However, I think this is more due to the fact that most of the music was written by Banks, thus, these harmonic progressions have more to do with his style of writing, than to a deliberate attempt to provide unity.

However, this in no way implies that the music is not worthy of attention. In spite of being a collection of musically unrelated songs, their ability to convey the images suggested by the lyrics and the overall plot is remarkable. The unity and cohesiveness of the work as a conceptual album, was achieved despite the challenges that band members had to confront at the time of writing and recording the work.

Much of the analysis that follows, is based on an excellent chapter called “’Counting out time’; The Lamb, song by song” from the book “Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” by Kevin Helm-Hudson. As I’ve done with previous analyses, I have selected the elements that provide a better understanding of the work, and excluded the more technical discussions.

Because of the simple expanded song format of most of the songs, I will not go into a structural analysis of each song. Doing so would not provide much in terms of enhancing the listening pleasure of these pieces. Instead, let’s discuss some interesting features in selected songs.

One interesting characteristic of “The Lamb” is that it is full of references to songs of the 60’s. Let’s look at them:

At the end of “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”, as the song is fading, we can hear a musical and lyrical quote from the 1963 Drifters hit “On Broadway”

“Broadway Melody of 1974” ends with an intertextual song reference: “Needles and Pins” written by Sonny Bono and Jack Nitzsche, a song by The Searchers from their album “Needles and Pins” that was a UK #1 hit in 1964.

During “The Cage”, there is a clear reference to the famous song “Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head” from Burt Bacharach and Hal David, although at a much faster pace:

Finally, the closing line of the lyrics in the album on the song “It”: “It’s only knock and knowall, but I like it” refers to the Rolling Stones’ 1974 hit “It’s Only Rock and Roll”

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

Written in a simple song format (AABA + a fading out Coda) and in straight 4/4 beat, this song is nevertheless full of creativity and strength. If you have followed all previous analysis up to date, you should be able to identify each section yourself. Feel free to give it a shot and post it in the comments section. The fading Coda is where the hit from The Drifters in quoted.

Upon exiting the subway, Rael describes what he sees in the streets of New York City, just before being thrown to the afterlife by the sudden blow of death.

Fly on a Windshield / Broadway Melody of 1974

Over a beautiful and dreamy guitar, complemented by voice mellotrons and electric piano, Rael describes how the wall of death descends. Only he seems to be aware of what is going on and, as he tries to escape, a strong wind carries a pile of dust that settles on Rael’s skin. He struggles to keep walking but is eventually paralyzed.

The sudden irruption of guitar, drums and bass, effectively portray the moment of the impact with the wall, throwing Rael directly into the first, or Chikhai Bardo.

As already discussed, this Bardo is characterized by a strong disorientation – earthly images flowing, as Hackett plays a solo (reminiscent of the “Shadow of the Hierophant” from his “Voyage of the Acolyte” album) and Rutherford establishes a strong harmonic pedal.

It is important to note at this point, that this resource – the harmonic pedal – is used several times very effectively throughout the album. For a discussion of what a harmonic pedal is, please refer to the analysis of Starless.

The harmonic pedal is maintained throughout “Fly on a Windshield”, until, at 2:31 it finally resolves and, through a series of modulations, starts another beautiful harmonic pedal, now the guitar doubling the bass, as Rael starts to describe a surrealistic succession of images. Note that the harmonic pedal, now supported also by the drums, obsessively repeat a syncopated rhythmic that will remain constant until the final section (first appearance of the “swoon” music). This resource helps to portray the tension experienced by Rael as he is sucked into the first Bardo and witnesses “echoes of the Broadway everglades”.

Holm-Hudson makes a detailed description of the characters that appear in this surrealistic parade. It is worthwhile to summarize these references because I believe they enhance the appreciation of the lyrics and the song:

- Lenny Bruce – a comedian known for his darkly satirical humor, was imprisoned for obscenity in 1961.

- Marshal McLuhan – a Canadian sociologist and pop-culture artist. Best known for his concept of the “global village”.

- Groucho Marx – no introduction needed…

- Caryl Chessman – an American criminal convicted on 17 charges of kidnapping, robbery and rape. He was executed in 1960. Chessman was one of the first people to die in a gas chamber. “peach blossom and bitter almond” is the characteristic smell of cyanide gas.

- Howard Hugues – well known American millionaire, who was convicted of fraud in 1972

The lyrics finish with the already quoted reference to the song “needles and pins” which make an obvious reference to the use of heroin.

Let’s revisit the lyrics with this additional information as we enjoy Nathaniel Barlam’s interpretation in this illustrated version:

Cuckoo Cocoon

This song marks the beginning of Rael’s voyage into the Chönyid Bardo. His consciousness is finally gaining an understanding that he is not physically alive anymore: “don’t tell me this is dying, ‘cos I ain’t changed that much”. It is interesting to point out that Rael is aware of himself in the afterlife: “No – I’m still Rael…”. This song features the only flute solo on the album.

In The Cage

This song, together with “The Colony of Slippermen”, is the most progressive in terms of its structure. It features an expanded format with an elaborate solo and it clocks over 8 minutes.

“The Cage” starts with a harmonic pedal and note that the rhythm of the bass resembles a heartbeat. This is yet another parallelism with “A Passion Play”. This rhythm effectively portrays Rael’s anguish as he starts to sense that something is going wrong: he starts to experience what, according to “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, would be a series of hallucinations based on his karmic balance.

After the first synthesizer solo, note that in minute 4:10, the mood of the piece changes completely in order to represent Rael’s first encounter with his brother John (his Higher-Self). Banks’ organ playing style, which up to that moment was percussive and syncopated, changes to sustained chords, resembling a church organ. This clever change brings a sort of “liturgical” atmosphere to the moment when Rael transcends his fear, and sees his brother John.

Eventually, exactly as it is described by “The Tibetan Book of The Dead”, as Rael sees his brother John disappear, the hallucination stops, and he ends up spinning like a top.

The piece ends with one of several ambience passages where the band would relax from the strictness of written music and allowed themselves some freedom. In these episodes, the timbres and effects would have predominance over harmony, melody and rhythm. Probably these interludes were created to fill some empty space, once they decided to turn “The Lamb” into a double-album. Some also have the purpose of allowing Gabriel to change costumes during the live performances.

The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging

Following the analogy with the events described in the Chönyid Bardo, Rael goes from one hallucination to another. This time, he witnesses a vision of humanity, where the vast majority of souls, attached to their most basic desires, are easily manipulated and controlled. He senses the need to transcend and, as he sees his brother John with a symbol of perfection stamped in his forehead (9 which is 3×3), he is able to run away from this hallucination.

This song features the first instance of Peter Gabriel’s voice being processed by Brian Eno – the “Enossification”.

Brian Eno’s “Enossification”

Gabriel met Eno at Island Studios during the mixdown sessions. Collins described this on an interview for Modern Drummer magazine:

Eno’s treatments of Gabriel’s voice on this track are similar to those on Eno’s own “The Fat Lady of Limbourgh”.

Once liberated from the second hallucination, Rael experiences a series of flashbacks from his most recent incarnation. Again, note the striking similarities with Ronnie Pilgrim’s experience when he witnesses his life as it is being assessed by the judges in the “Memory Bank”:

Back in N.Y.C.

This song represents the strongest departure from Genesis traditional style. Lines like “I’m not full of shit” would have been unconceivable in previous albums. It clearly shows Gabriel’s desire to move away from the “fairy-tale” world and move into the realm of harsh world reality.

Note that the contrasting section – cuddling the porcupine – features again the vocal effects of Brian Eno. This effect could have been used to represent a conflict between Rael and his higher-self:

- “He said I had none to blame but me” – his heart is “deep in hair. Time to shave it off.”

To which Rael replies:

- “No time for romantic escape when your fluffy heart is ready for rape. No!”

After a brief introduction in 6/8, the song goes into a pedal point groove in 7/8. Notice that this odd meter is maintained throughout the song with two brief one-bar diversions to 6/8 in the “porcupine” section. Can you find them? Just post their exact location on the comments section.

Hairless Heart / Counting out Time

“Hairless Heart” is a short and beautiful interlude that separates Rael’s 2 flashbacks. It was probably written by Hackett and was never played live again by Genesis after “The Lamb” tour.

“Counting out Time” was one of the 2 pieces written entirely by Gabriel. The structure is a simple song format, in a metric of 4/4 and based on a harmonic progression used regularly in rock and pop songs. Holm-Hudson compares it with Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale” and Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman”. But this is no ordinary pop tune. Listen to the song but paying attention only to the bass. You don’t often see such an elaborated and rich bass pattern in a love song. Rutherford’s arrangement of this song reminds me of Paul McCartney’s ingenious bass lines, for example, on Abbey Road’s “Something”. Also, look for the change in meter to 5/8 at the beginning of the instrumental interludes that separate the song sections.

As a final curiosity, for the light-hearted guitar solo, Hackett processed his guitar with an EMS Synthi Hi-Fli guitar synthesizer, an early multi-effects pedal introduced in 1973. Again, pay your attention to the elegant bass line:

Steve Hackett’s solo with the EMS Synthi Hi-Fli guitar synthesizer

The Carpet Crawlers

As already mentioned, it is amazing that such a beautifully crafted song was written in a rush. It is a clear demonstration that Genesis members were at their creative peak during the creation of “The Lamb”.

Structurally, it consists of simple repetitions of verse and chorus.

It is at this point in the story where Rael starts to exercise his will. Up until know, he had been a passive witness – with the exception of his running away in “The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging”. Now he starts to enquire and tries to find out what the carpet crawlers are doing:

Note that, for the first time since the beginning of the album, there is a reference to the lamb: “There is lamb’s wool over my naked feet,”. Here’s another exception to the otherwise independent treatment of the songs in the album: the harmony behind this line, is identical to the passage in the first song when Rael encounters the lamb in the middle of a street in NYC. Let’s compare both fragments:

Lamb’s leitmotiv

So, this arpeggiated passage could be regarded as some sort of “leitmotiv” of the lamb. Very interesting…

The Chamber of 32 Doors

This is the other song totally written by Gabriel and, arguably, one of the most beautiful and well-written in his career.

Rael finally makes it to the top of the stairs and enters a large hemispheric chamber with 32 doors around its circumference. The critic Francoise Couture makes a very interesting remark:

As I already explained, Rael must now decide which course to take as a next step in the evolution of his soul. Again, Banks’ use of the organ using sustained chords as opposed to rhythmic and percussive provides a very fitting liturgical setting for this part of the story. Also, notice that the song starts with a guitar solo, which is a rarity in the album. Finally, notice the reappearance of the mellotron, which had been absent since “Fly on a Windshield”.

Lilywhite Lilith

With the help and guidance provided by this blind woman, Rael decides the course of his next incarnation and this marks the end of his transit in the Chönyid Bardo.

The piece features yet another appearance of the use of harmonic pedal. Notice that the bass is steady at a single note, although every pedal note is preceded by 4 introductory notes. The use of this harmonic resource allows the piece to merge naturally into one of the two reprises in the album where music material is shared among different pieces: “Broadway Melody of 1974”, also based on the use of harmonic pedal. Let’s compare:

Lilywhite Lilith Broadway Reprise

And this reprise ends with the second appearance of the “swoon music” that separates the second and the third Bardo.

The Waiting Room

Most of you have surely heard stories about people describing a tunnel of white light during near-death experiences. Well, amazingly, “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” written in the VIII century, also describes tunnels of light at the moment of death, and just before being reborn.

After deciding the starting point of his new physical life in the chamber of 32 doors, Rael was ready to be born again and the white tunnel appeared. However, he was not ready to go back yet and, afraid of the approaching light and the sounds, he throws a stone at the source of light and interrupts the process.

This piece is one of the very few instances in Genesis career where the musicians were open to the experience of free improvisation.

Anyway

The ceiling collapses as a result of Rael’s decision to destroy the source of white light and he is, again, trapped. But unlike “The Cage” where Rael showed a clear desperation, now he approaches this situation from a calmed philosophical perspective: “How wonderful to be so profound, when everything you are is dying underground”.

Citing Holm-Hudson:

Here’s “Frustration”:

The Supernatural Anesthetist

As I explained earlier, this episode bears a striking resemblance with The Tibetan Book of the Dead’s description of Yama.

The prominence of the guitar and the overall writing style seems to suggest that Hackett was the main author of this piece. Originally conceived as an instrumental number, Gabriel attached a few verses in the beginning. Although it is a fine piece in his own right, I don’t think in this case the music makes an appropriate description of the story line. One can hardly imagine the encounter with Yama under such a musical setting – imagine that this was the background music to this scene in a film. It certainly wouldn’t work… I suspect that again this was a result of their pressure to finish the work on time. Under different circumstances, an entirely different piece would have been written to describe this scene and Hackett’s piece would have been placed elsewhere; maybe even on another album.

The Lamia

On the lyrics of this wonderful piece, one can clearly see the influence that Jung and “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” had on Gabriel at the time of his writing. Much of the imagery, although not the story per se, is derived from a poem by John Keats written in 1819 called “Lamia”.

On his work “Symbols of Transformation”, C.G. Jung makes several references to the “Lamia”. In fact, he also mentions “Lilith”, who is some sort of “demon-wife” that was married to Adam before he knew Eve.

But the most interesting connection, is with “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”. The “Sidpa Bardo” or “bardo of rebirth” features karmically impelled hallucinations which eventually result in rebirth, typically Yab-Yum imagery of men and women passionately entwined.

Also, remember that “The Lamia” evoke the “blood-drinking” wrathful deities referred to in this book.

Musically, this piece is among the strongest in the album in terms of its ability to complement the lyrics and the plot.

Quoting Holm-Hudson:

Also, the arrangements are carefully crafted. Note, for example, the sudden surge of a mellotron when the Lamia introduce themselves to Rael. After the death of the Lamia, a voice mellotron accompanies Rael’s mourning, as if representing the departed spirits.

The Lamia Mellotrons

Also, the transformation of the Lamia is represented by a musical transformation of the interludes that precede each return to the verse. The first time at 2:11 the interlude is presented in piano solo. The second time, at 4:54, it is “transformed” by adding a synthesizer. Let’s listen to them:

The Lamia Interludes

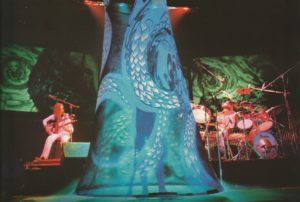

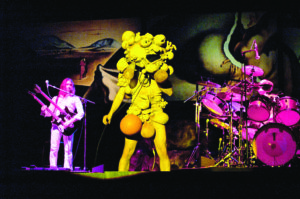

During “The Lamb” tour, a multi-colored fabric descended over Gabriel, obscuring him from view.

After “The Lamb” tour, the song was never performed live again by Genesis.

Silent Sorrow in Empty Boats

I have nothing to add to Holm-Hudson clear and concise explanation:

The song was never performed live again by Genesis after “The Lamb” tour.

The Colony of Slippermen

This photo is from a performance of the cover band “The Musical Box”, who used exact replicas and sometimes even the original stage design and costumes from Genesis.

This piece, together with “The Cage” is the most progressive piece in terms of its construction. It is really a mini-suite comprised of three parts: “The Arrival”, “A Visit to the Doktor” and “The Raven”.

As in “The Lamia”, Gabriel takes his inspiration from English Romantic poetry. In this case, the opening stanza parodies “William Wordsworth’s 1804 poem “Daffodils”:

“I wander’d lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills….”

The introductory instrumental section that precedes “The Arrival” is yet another fine example of the music accurately describing the events of the plot. The glissandos in the guitar, the portamentos in the synthesizer, the choice of timbres, everything is carefully selected to represent the moment when Rael, already a deformed slimy creature (although his is still not aware of it) jumps out of the pool and starts wandering until he is welcomed as a newcomer to the colony.

“The Arrival” and “A Visit to the Doktor” do not share thematic material, although they are linked by the similarity of the arrangements. It is in “The Raven” where the musical ideas are re-exposed giving musical coherence to the mini-suite.

Compare these sections on “The Arrival” and “The Raven”

“The Arrival” and “The Raven”

And “A Visit to the Doktor” with “The Raven”:

” Visit to the Doktor” and “The Raven”

In the Resources section you will find a link to the piece “The Light” that was the source for much of “Lilywhite Lilith” and “The Raven” section of this song.

Ravine

As with “Silent Sorrow on Empty Boats” this song serves the utilitarian function of allowing Gabriel to change out of his slipperman costume. Both songs were added to the album late in the recording session when the band realized that they needed to give Gabriel some time for his costume changes.

The Light Dies Down on Broadway

This song, together with “Lilywhite Lilith”, is one of the few examples of shared music material throughout the album. In this case, what we have is a double-reprise featuring music from “The Lamia” and “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”.

As noted earlier, the lyrics of this song were not written by Gabriel but by Rutherford and Banks. It is written in third-person, in contrast with the largely first-person voice in the rest of the album. The most transcendental moment of the plot occurs in this piece.

Quoting Holm-Hudson:

The piece is constructed using first material from “The Lamia” followed by “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”. Let’s take a closer look:

This is the section that reprises “The Lamia”:

This is the reprise of “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”:

This structure repeats and the piece finishes with an instrumental coda.

Riding the Scree

This piece is based on an ostinato built around an irregular metric that is identical to “Apocalypse in 9/8”: a metric of 9/8 subdivided as: 2+2+2+3. This pattern is maintained by sustaining chords all the way until the end, but it doesn’t appear to be so because all members of the band “play around” with this metric and perform a number of metric displacements. If you can follow the ostinato chord pattern, and count: 2+2+2+3 you will be amazed at how the metric displacements can be perceived very clearly.

If you don’t have a clear understanding of what a measure is, you might want to follow the explanation given on the analysis of Close to the Edge Part / 1 (starting at minute 24).

You can also refer to the analysis of Supper’s Ready Part/2, where I help counting this exact metric in “Apocalypse in 9/8”.

Holm-Hudson comments that the line “Evel Knievel, you got nothing on me” refers to a motorcycle daredevil by that name, that attempted to jump across the Snake River Canyon is a special rocket-propelled motorcycle. The jump was highly publicized and a spectacular failure. This event took place on September 8, 1974 so this allows to determine that the lyrics, at least in this case, were written late in the recording sessions of “The Lamb”.

In the Rapids

As is the case with “The Supernatural Anesthetist” this piece appears to have been written in a rush or without a specific part of the plot in mind, and was later used for the final part of the album. Again, the pressure to finish the album on time might have determined this outcome. Even though the piece slowly develops a climax, the lyrics: “the rush of crashing water surrounds me with its sound” is hardly represented by the mood of the music. Again, imagine that this was the background music to a scene in a film where two people are desperately trying to grab on to whatever they can, as violent rapids take them downstream. It just wouldn’t work.

I also believe that the intense moment when Rael’s conscience darts between him and his Higher-Self, reaching enlightenment as his consciousness is finally merged with Oneness, deserved a more intense musical development.

It

From the perspective that I have chosen to interpret the story, it is clear that “It” refers to “all there is” – to Oneness.

From a musical point of view, it is interesting to note that the song is built using the same two initial chords from “Watcher of the Skies”. Genesis was very aware of this link between the two songs because “Watcher” was frequently an encore during “The Lamb” tour; thus, “It” and “Watcher” were played together. In fact, after Gabriel’s departure, Genesis would occasionally play a medley composed of “It” with an abbreviated version of “Watcher”.

Let me finish the analysis of “The Lamb” with C.G. Jung’s description of when “the summit of life” is reached. Again, another example of his influence in the writing of Gabriel:

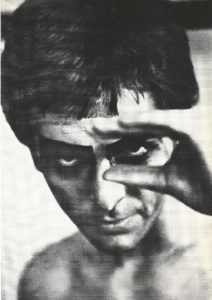

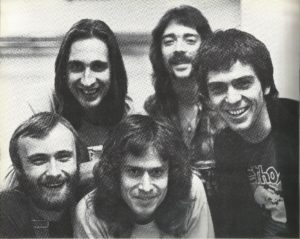

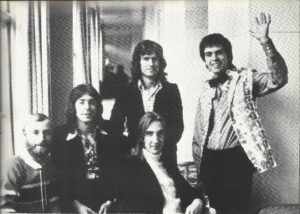

The photo above was captured by Armando Gallo at the Savoy Hotel during a presentation of Gold Albums for “The Lamb” and “Selling England”. It was Gabriel’s last public appearance with Genesis before he left the band.

Resources

This analysis would not have been possible without the solid foundation laid by Holm-Hudson’s excellent book ”Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway”. Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series. First Edition. It can be purchased here.

Genesis photographs were scanned from my personal copy of Armando Gallo’s book “Genesis I Know What I Like” D.I.Y Books, 1980. It can be purchased here.

The background music used is:

- The piece “Dionisio de Magnesia” by the Spanish band Tricantropus, from their album “El Sueño de Arsione”

- The piece “L’etau Familial” by the French band Yang, from their album “Machines”

- The piece “Hydraulic Fracas” by the USA band Zhongyu, from their album “”Zhongyu” Is Chinese For “Finally””

- The piece “Structure 5” by the Spanish band Kotebel, from their album “Structures”

- The piece “Sleepwalking the Dog” by the USA band Zhongyu, from their album “”Zhongyu” Is Chinese For “Finally””

- The piece “9/8 Variations” by the French band Yang, from their album “The Failure of Words”

- The piece “Zodiac” by the USA band Ut Gret, from their album “Ancestor’s Tale”

- The piece “De la Mélancolie à la révolte” by the French band Yang, from their album “Machines”

- The piece “3éme Messs” by the French band Yang, from their album “Machines”

It is extremely difficult to find The Lamb’s story in the Internet. Of the several links referred to in Holm-Hudson’s book, the only one still active (at the time of writing this article in October 2017) is:

http://www.ferhiga.com/progre/notas/notas-genesis-tlldob-ingles.htm

“Lilywhite Lilith” was a reworking of an early Genesis song called “The Light” (Bowler and Dray, 1993, p. 94). That early song provided the guitar riff and the verse melody of “Lilywhite Lilith” (Russel, 2004, p. 203). Banks remembers:

The “little triplet section” to which Bank refers also wound up recycled for “The Lamb” as “The Raven” section of “The Colony of Slippermen.” (Holm-Hudson, 1980 , p. 83).

This is the only recording of “The Light” known to exist, from a performance at the La Ferme V club in Belgium, on 1971:

There are no high-quality video recordings of “The Lamb” tour. This is one of the better ones that you can find in YouTube:

The entire “Lamb” performance at “Shrine Auditorium” in Los Angeles on January 24th 1975, is included in the Genesis Archive 1967-75 Box Set.

You can listen to this performance in public YouTube links but if you like it, please purchase the box set!

As a minor side note, the film Sorcerer was a remake of a French film called, Le Salaire de la Peur, The Wages of Fear (1953) which is considered to be a huge classic by International movie fans. Unfortunately, the remake did not capture that magic, but many years later, Sorcerer is considered to be a cult classic here in America.

Very interesting. Thank you very much!

I must say that I never associated the Book of the Dead, (which I read a long time ago with the Genesis’ Lamb. As I recall it wasn’t the easiest book to read, I have to revisit it. Saying all that, reading this article a few times it makes a lot of sense to me. Well simply because… listening to the album I couldn’t make sense of it lyrically. Yes, it definitely sounded different from let us say, the Musical Box, but to me the Colony of Slippermen sounded like another fantasy number with psychedelic elements maybe? Some of it sounded downright creepy, with a horror element, excuse me if I am way off on this. Anyway I was a bit lost with the lyrical context but to be completely honest I did not care too much. I cared more about the melodies and the music. Although I understood ‘IT’ lyrically and instinctively. But now, I feel there is a bigger story told here that is actually more cohesive then I ever thought, thanks! Also… It is a very wierd coincidence that the film I mentioned, the original French name, “The Wages of Fear”, (and the main theme of the movie as I remember) that title alone in fact ties in with some of the topics being discussed here and delt with on the album in a more general sense. After all it is a great universal topic isn’t it? The more basic fears of danger and death, but ultimately also the fear of the unknown.

Personal note: I think this is one of the few times I actually commented on the Classic as opposed to the Article simply because they are so well researched and there is not much to add. This time I kind of tried to go back to some of the feelings I had when I was younger, and also to the gut feeling of the piece, in fairness I paid attention to the lyrics less and to the music more with some of this stuff. Just as an example lyrically, I undersood Tarkus very clearly, the Last Supper too, Close to the Edge was no problem, I could deal with Jon’s poetic librities, Passion Play was somewhat brooding, probably did not get all the refrences that Ian made, Lamb was probably the most complex for me in words to totally grasp. Now I understand it much more, thanks!